“It was dead before we heard the smack of my bullet hitting it”

Canadian hunter Arnold Alward was one of the first hunters ever awarded SCI’s top prize, the World Conservation & Hunting Award. He was also the first Canadian to win the Weatherby Award, the industry’s ‘Oscar’. He has been known to go hunting as often as 13 times a year.

Alward has been on at least 131 trophy hunting trips on 6 continents during his lifetime. Along the way he has hunted the ‘Big Five’ (lion, African elephant, leopard, rhinoceros and cape buffalo), and shot 22 different species of pygmy antelope, 21 types of wild goat, 20 different kinds of wild sheep, and 50 species of antlered animals.

He has several animals in SCI’s Records Book, including two leopards shot in Zambia, a white rhino killed in South Africa, a Spotted hyena from Ethiopia, an African Elephant shot in the same country, a Cheetah hunted in Namibia, and a Lion from Tanzania.

In total, 277 of his trophies are in Safari Club International’s book – 62 of them are ‘Top Tens’.

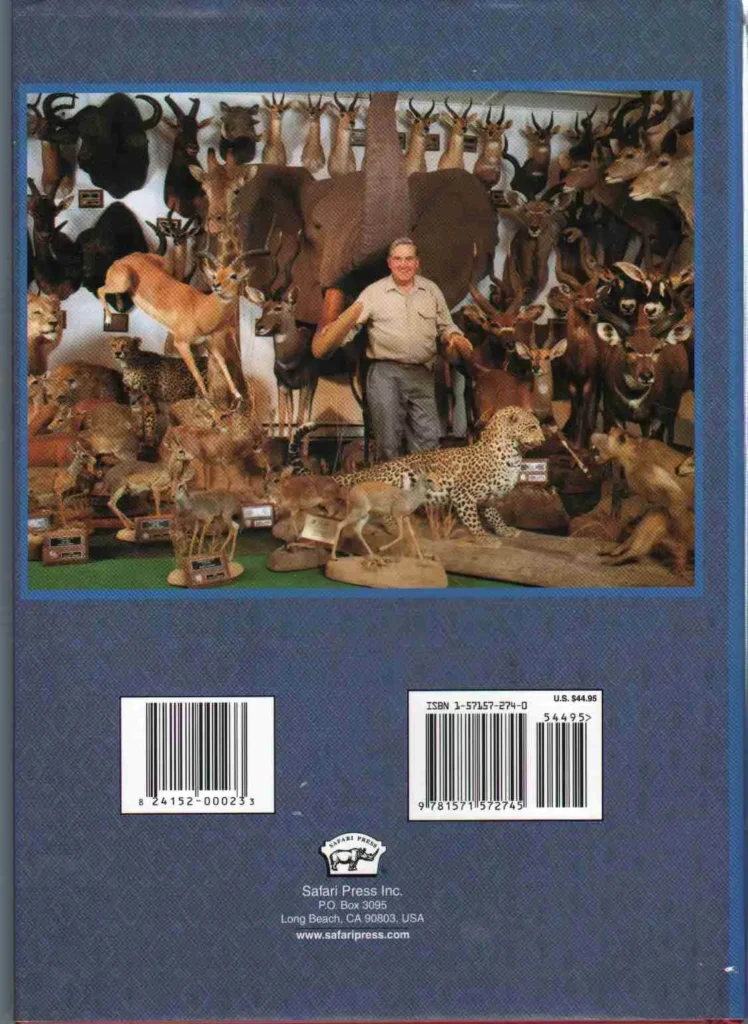

Alward has 350 trophies of animals on display at his home in New Brunswick, spanning 285 different species. His favorite trophy is an elephant whose tusks weigh a combined 225 lb.

His hunting spree was triggered by the deaths of his parents, a sister and daughter in quick succession. He sold his businesses and went hunting almost without interruption for the next 18 years.

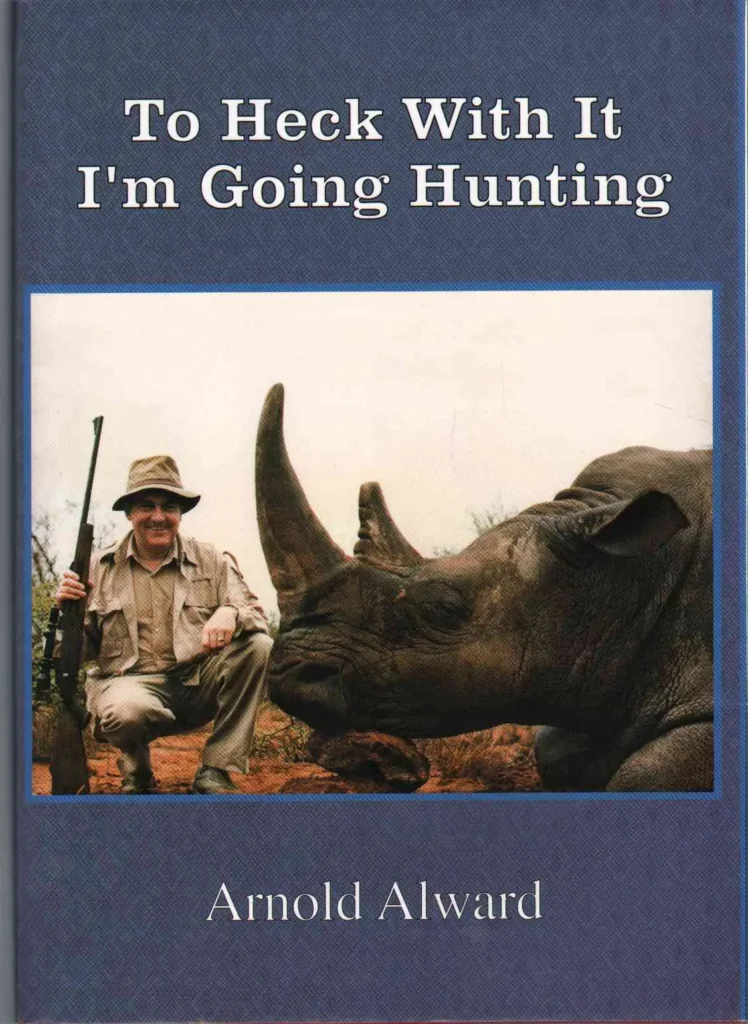

He later wrote a book about his expeditions called ‘To heck with it, I’m going hunting.’ It tells of how he shot “nearly all the world’s important big-game species.” [1]

The cover features a smiling Alward kneeling next to the head of a rhinoceros he has just shot. The back shows him standing amidst a crowd of trophies including the bodies of lions, cheetahs, leopards, hyenas, baboons, and various deer and antelopes.

Alward smiles as he rests on one of the giant tusks protruding from the head of an elephant behind him. The base of its trunk appears to be resting on his head. Next to it, the head and neck of a giraffe reaches out from the floor towards the ceiling. On the inside flap, we are told that Alward is “an avid conservationist”.

His brother has traced their family origins back to the Anglo-Saxons. An English clergyman named Thomas Alward was the first of the Alwards to arrive in North America. “Our ancestors were among the seventy thousand Tories who remained loyal to King George III and fled the Thirteen Colonies into what was then called British North America.”

As a child on the family farm, he snared rabbits and sold them for 25 cents a pair. He would then hunt rabbits and racoons with a .22 rifle. From there he moved into deer, “hunting them as much as was legally possible near our home every fall.”

Alward’s father ran a business selling agricultural lime. He joined the family business, helping it to expand into fertilizer, concrete aggregate, and road construction materials. The company soon built its own lime processing plant and became a multi-million-dollar business.

The deaths of his parents, sister and daughter changed everything. however. “I decided to sell the companies and follow my lifelong love for hunting”.

He and his wife flew to Africa, where they are overwhelmed by the sight of so many different animals. “In addition to the Big Five (lion, buffalo, leopard, elephant, and rhino) and giraffe impala, warthog, and wildebeest, we saw animals that I never knew existed until then.”

A plan starts to form in his mind. “I decided that all of this was too good not to be shared. Wouldn’t it be great if someone assembled a collection of mounts of every African animal so that people who couldn’t go to Africa could see them up close?

“I had no idea how many types of game animals there were on the planet, but I was determined to find out.”

He decides to set a target of shooting animals from 200 different species.

“The experience had changed my life. An elk hunt I’d already scheduled for that fall in Montana would launch my quest to assemble this great collection of the world’s game animals. I had to start somewhere, and North America was as good a place as any.”

Shortly after, Alward hears about Safari Club International from a friend. It results in Alward attending his first SCI convention the following year.

“It was like a kid walking into a toy store for the first time, and it hardened my resolve to begin the quest to collect two hundred specimens of big-game animals.”

He ends up bidding $65,000 to buy a rare, double-barreled buffalo rifle at the auction SCI holds every year to raise money for its lobbying work.

Alward learns about Safari Club International’s Record Book and World Hunting Awards.

“I spent a lot of time with the SCI All-Time Record Book of Trophy Animals, browsing the pages of its Africa edition, comparing the animals I had seen in Kenya with photos of the animals taken by SCI members.”

He adds: “I used the record book, as well as Safari magazine and the SCI World Hunting Awards programs, to plan my hunting.”

The following year, Alward takes off to Africa with his sons for what will be the first of countless hunting trips that were to occupy him over the next 18 years. He stops off in London, where he asks a fellow hunter to keep custody of the rifles he has brought with him before the next leg of his journey. Soon after, he arrives in Zambia – and shoots the first of many leopards, followed by a buffalo and a hippopotamus.

However, the hippo has been killed not as a trophy – but to serve as bait to lure a lion into a trap. Alward and his hunting guide have built a screen near where the hippo’s body has been left. It isn’t long before it attracts the attention of a large-maned male.

As he looks out from behind the screen, Alward can see the lion feasting on the hippo’s carcass. It is joined shortly afterwards by a female.

“I saw a lioness effortlessly rip off a good-size hunk of hippo meat. She then walked over to the front of our blind, plopped down, and began eating – just three or four long steps from where we were standing.”

Alward can scarcely believe his luck.

“I could see the lion clearly in my scope.

“I put the cross hairs on the lion’s shoulder, aiming for where I thought the center of the opposite shoulder would be, and fired.”

The response is immediate.

“The lion jumped straight up and flopped around on the ground, roaring as it died.

“I had taken my first African lion.”

His hunting guide tells him to shoot again, just to be sure.

“Russ had me fire into its spine for insurance.”

Alward now admires the slain creature in awe. “It weighed more than four hundred pounds and was nearly as large as a spike elk. It had a massive head, with very long teeth.

“I wondered what had happened to the lionesses, especially the one that had been feeding near our feet.”

The hunt continues, and over the days that follow, Alward’s list of trophies mounts up.

“In addition to taking hippo, lion, lechwe, and crocodile at this camp, we also took two leopard, buffalo, bushbuck, warthog, wildebeest, waterbuck, zebra, puku, impala, oribi, baboon, and greater kudu.”

As with the lion, Alward and his team used baits to bring the leopards to them, and waited until nightfall to shoot the nocturnal cats. “We took the leopards at sundown, luring them to my rifle with impalas we hung in trees.”

The hunt had taken just 12 days.

Before his trip, he had bought two licenses to shoot each of the species on his shopping list. “I shot one of each, and my sons shared the other permits.”

At the end of that season, Alward writes: “I don’t know how a first hunting safari could have been any better than this one. We took twenty-one different types of animals – including three members of the Big Five – and most of them qualified for the SCI Record Book.”

Alward decides to make hunting rhinoceros his next priority. He flies to South Africa and borrows a .375 H&H Magnum from a local professional hunter. “I planned to take as many of the country’s unique game species as I could, especially the white rhino.”

He goes rhino hunting with Johnny Vivier, one of the country’s top hunting guides. Alward stays at a farm which has several rhino bred for hunters to shoot. They drive to the area where the rhinos were roaming. Vivier points one the one with the longest horn to Alward.

“See that one on the left, the one with the longest horn?”

“Yes.”

“That’s yours.”

The pair quietly close in on their target, until they are just 30 yards from the animal. The rhino in Alward’s sights turns slightly to one side.

“I aimed about one-third up its chest, just behind the shoulder, and fired.”

There is a burst of dust from the animal’s side. The rhino is startled and makes to run away. “He won’t go far,” says Vivier.

The rhino comes to a halt three hundred yards away. Alward and Vivier eventually catch up with it.

“I shot it again in about the same place, and it ran off again,” says Alward.

The rhino runs away again, but this time only goes 100 yards.

“It went down in a cloud of dust. I now had four of the Big Five.”

It is just 9.30am in the morning, and Alward already has his prize trophy. He bends down and poses delightedly for a photograph with his victim, rifle in hand.

Shortly afterwards, he shoots two small antelopes, and goes off in search of zebras.

The following season, Alward goes on no fewer than 13 separate hunting expeditions. It begins with a cougar hunt. (The species is commonly called a mountain lion in North America, and a puma in South America.) The hunt takes place in January, in the state of Colorado.

The hunting company he has hired uses packs of dogs to locate and then chase cougars up trees, making it easier for the hunter to shoot them. The dogs had found cougars on both of the first two days of the hunt but then lost them.

Alward’s luck eventually changes. “It wasn’t until about 11 o’clock on the third morning that the dogs were able to catch up with a big tom and tree it.

“There is no hunt more exciting than following hounds,” he adds.

The cougar is trapped about 30 feet up in the tallest tree. The hunting guide ties up his dogs a little way away – “he didn’t want me to drop a wounded lion on top of them.”

Once the last dog has been rounded up, Alward takes up position.

“I killed the lion, a big male with a long, thick, golden coat. Paul rewarded his dogs by allowing them to maul the cat. I was worried that they might rip it apart, but they didn’t damage the hide.”

They load the cougar’s body onto the back of a snowmobile so that the guide can skin it. Alward says he “enjoyed the experience.”

He kills another cougar some years later in South America.

Alward’s next trip takes him to Australia and New Zealand, countries without native ‘big-game’ animals but which had them imported by early colonial explorers and settlers. They included water buffaloes brought over from India, many of which escaped into the wild.

Early hunters also deliberately released deer from Europe, mountain goats from the Himalayas, and even elks and moose from North America, although the latter failed to thrive.

Alward hires a helicopter to help him find animals to shoot. He is able to shoot a Chamois, a Tahr, and a thirteen-point red stag. He also shoots a turkey, hedgehog, weasel and an Australian possum.

“That afternoon I added a wallaby to my collection,” he notes with satisfaction.

Before flying back to Canada he writes: “I’d taken all fifteen species introduced to the South Pacific, and all qualified for the SCI All-Time Record Book of Trophy Animals.”

Soon after he completes half of SCI’s ‘Grand Slam’ of North American wild sheep.”

His pilgrimage continues. “I had booked four back-to-back hunts during thirty-two days beginning 8 September.”

On one of the first trips he shoots a moose. “I found a good rest and shot it low and just behind the shoulder as it was quartering away. It ran only about thirty yards before it collapsed.”

It’s a little smaller than another one he had shot previously. “I wasn’t disappointed, though.”

He spots a pair of coyotes afterwards. “I shot both of them.” A bighorn sheep soon succumbs to his rifle.

He eventually flies home. “I had been gone thirty-two days, had hunted nonstop, and had added sixteen species, including the exotics, to my collection. I had all the skins and horns shipped to Verrips Taxidermy Studio in Adkins, Texas.” He receives the finished trophies seven months later.

“I’d had a busy year,” he concludes.

The following season’s priorities include a big tusker elephant and a brown bear. He flies to Ethiopia in pursuit of the first.

He sees several whilst out in the field, but passes on them all because their tusks aren’t big enough. Eventually, however, he sees one that is to his satisfaction. He waits until the big male is in his sights.

“I aimed at a spot behind its shoulder and slightly low to compensate for being so close. When my bullet smashed into its lungs, the elephant trumpeted and whirled before crashing off through the brush.”

He wanders over to the elephant, dead on the forest floor.

“It was a huge animal, and its tusks were even better than I had hoped. The larger weighed 115 pounds; the other was 110 pounds. They would receive the number one SCI Major Award for Africa at the next SCI Convention.”

Alward poses for photos with his kill. The following day, 8 skinners are sent to start taking the body parts Alward wanted to take home, including the tusks, an ear, “and the four feet, which I intended to have made into stools.”

He shoots some more animals over the days that follow, before heading for home.

“I had taken seventeen animals on this safari, including the huge elephant that completed my Big Five of the dangerous big-game animals of Africa.”

It isn’t long before he heads off once more in pursuit of further trophies to add to his growing collection. This time he is in his native Canada, and is in search of a moose. It isn’t long before one turns up almost outside his tent. “I passed up that bull, and we found a better one an hour later.”

The new animal can be seen hovering by the side of a lake.

“I shot it with my 7mm Remington Magnum, and it went down. It was a beautiful bull with an antler spread of 59 ½ inches, an excellent western Canada moose.”

They cut off its antlers and skin the animal before heading off back to camp.

The next day they spot a bear. It’s just what Alward had been looking for. “After a quick look in the spotting scope, I decided to take it.

“My first shot broke both shoulders, and it went down roaring. My second shot killed it.

“Although I was looking for a much bigger bear, I was pleased with this one.”

“I was especially impressed with the size of its head and feet,” he adds.

As had by now become his habit, Alward starts the following year at SCI’s Annual Convention, where a thousand or so hunting companies sell hunting adventure holidays. It is an ideal place for Alward to shop around.

The event also hosts Safari Club International’s awards ceremony, a glitzy gala dinner winner of the Oscars. Alward proudly collects his first SCI cumulative award, the First Pinnacle of Achievement.

Alward comes away even more satisfied with the next batch of hunting trips he has purchased.

“Before the convention ended, I had booked three separate African safaris, as well as hunts in Mongolia, British Columbia, and Mexico for later that year. These were in addition to the muskox and polar bear hunts I’d already planned for 1990.”

He succeeds in getting the polar bear he wants for his trophy room. Alward is photographed standing behind the fallen bear, rifle by his side. “Hunting polar bear in the high arctic with a dog team made for many new experiences,” he observes.

The next leg of his journey takes him to Namibia, where he shoots a cheetah. “I killed it with my first shot. While we were snapping photos, I spent a lot of time inspecting the cat. Its spotted coat was beautiful, and I could see why it was so prized when cheetah coats were fashionable for women.”

Alward wants to shoot another lion to add to his collection. “The first thing I did was shoot a hippo for bait.” However it only serves to attract hyenas and jackals.

He leaves Africa and returns to North America in search of more bears – specifically a bear over seven foot tall. Alward spends four fruitless days until he finally sees one to his liking.

“It was the best bear I had seen during the entire week, and I shot it.

“Although it was not as large as I had hoped to take at the start of the hunt, I was happy with it. Its hide was in good shape, and it had long, luxurious hair.”

He is satisfied with the result of that year’s hunting expeditions.

“I had hunted in Texas, British Columbia, the Northwest Territories (in Canada), and the Mexican state of Sonora in North America; Namibia, South Africa, and Zambia in Africa; and Mongolia in Asia – seven countries on three continents in 143 days – and had added forty more specimens to my collection.”

The following year brings new adventures, and trophies.

“I began the year by hunting wolf and lynx from a two-seat Super Cub in Alaska,” he says excitedly. Mission concluded, he flies to Equatorial Guinea. He has come in search of a Bongo antelope. Alward is deep in the forest with his guide when he spots one.

“I slowly brought my .300 Winchester Magnum to my shoulder, put the cross hairs on what I figured was the shoulder, and fired.”

The Bongo disappears into the forest. Alward is convinced he has hit him, though.

“After we had waited a few minutes to allow the animal to die or grow weaker, the trackers picked up the blood trail. Two hundred yards later, we found the bongo dead.”

Alward is able to inspect his new trophy close-up. “I was relieved to see it was a mature male that qualified for the SCI record book.”

A giant eland and a dwarf forest buffalo are next on his list, followed by a trip to Russia in pursuit of a Siberian brown bear, a moose, snow sheep and a reindeer.

“I had taken every animal I wanted,” he records afterwards.

From here, Alward flies to Spain to shoot ibex. “I found a rock I could rest my rifle on, used my jacket to cushion it, put the cross hairs on the billy’s spine, and squeezed the trigger. The ibex simply collapsed. It was dead before we heard the smack of my bullet hitting it.”

Another successful hunting season comes to an end. The following year starts well for him too. “A good start for me, with a Canada lynx in February and an Alaskan wolf in March.

”The lynx completed my SCI Grand Slam of the Cats of the World. A month later, with Dan Troutman’s Alaska Sport and Recreation, I shot a black male wolf and a red fox on the Ivishak River in the northern Brooks range.

“Taking that wolf meant I had collected forty different species and subspecies of the larger game animals in North America.”

Alward has now hunted on five different continents – North America, Africa, Asia, Europe, and Australia. Now it’s the turn of South America. He arrives in Buenos Aires, where he is met by a fixer who has helped him secure a permit enabling him to get his rifle through customs. He then sets off to a hunting estate on the Colorado River.

His first success is hunting wild boar from a baited stand. Next it’s the turn of a puma (cougar).

“We hunted the puma with a pack of hounds, driving around until we found a fresh track and then releasing the dogs and going off on foot through the brush.

“After several false starts, we hit a very hot track and spent the next three hours following the dogs before we heard them barking. The rest of that hunt was anticlimactic. The dogs had run a puma up a tree, and I shot it.”

Alward is determined to shoot a local Peccary, which would help him complete one of Safari Club International’s awards for shooting different kinds of wild pig species.

“We bumped into a herd of ten to fifteen animals, confused and running this way and that. I shot the largest I could see. It later would rank very high in the South American category of the SCI All-Time Record Book of Trophy Animals.”

At the end of his South American hunting tour, Alward reflects on his successes. “I had taken twelve different species in three weeks.”

Alward decides to fly back to Africa, this time to Tanzania. His primary goal is to shoot a giant Kudu antelope. However, he ends up shooting a lion first.

“While hunting for that kudu, Rainer (Alward’s hunting guide) and I drove up on a big lion. I’d taken other lion, but this one was a big one with an exceptionally thick golden mane, and I decided to try to take it.”

They parked their pick-up nearby, and walk back up to where they had seen the lion.

“When we were about fifty yards away from where it was standing under a tree, I shot it.

“As many lion do when fatally hit, this one leaped into the air roaring, then collapsed kicking where it had been standing.”

Alward spends the rest of the safari hunting for bushpigs, an animal he had unsuccessfully hunted on previous trips to Africa. This time he is in luck, however.

“The first pig we saw a female asleep under a tree. I carefully took another step and spotted the male. It was only twenty yards away when I shot it. I had broken my jinx!”

At the following year’s Safari Club International convention, Alward is presented with SCI’s Humanitarian of the Year award.

His globe-trotting exploits continue, with further trips to Spain and the Himalayas before he finds himself back in South America. Alward is presented with an opportunity to shoot a tapir – an unusual-looking, non-aggressive animal that looks like a cross between a hippopotamus, an anteater and a pig.

It’s a new species for Alward to add to his collection.

“I quickly moved to a small tree, used a bench to steady my rifle, and shot the animal. When it did not go down, Jose (his guide) and I ran after it. A hundred yards past where we had last seen it, we came upon the tapir again. This time my shot put it down.

“My tapir was a very large animal, at least 350 pounds, and six feet long. Its dark-brown hair was very short, and its feet and nose were unique.

“When my guides skinned it, I was surprised to see that its skin was nearly a half-inch thick. I had not planned to collect a tapir, but I was glad to have taken this one.”

His next stop is Kazakhstan to shoot a Mongolian saiga, a one-hundred pound antelope. He also shoots a Tur. From there he goes to Turkmenistan to hunt a Marco Polo argali, a Trans-Caspian urial and a Persian goitered gazelle.

The expedition is followed by one to Turkey to hunt a chamois, a brown bear and an ibex. He ends up shooting two ibexes, one of which qualifies for the SCI Record Book. The year has now come to an end.

“I’d had an interesting year, hunting in ten countries on four continents. I’d taken thirty-four specimens,” he says.

The following year takes Alward to new destinations in China to hunt a Gansu argali, and also to Pakistan. Alward decides to go back to Canada to hunt some more bears as well. It’s coming to the end of winter, when bears begin to emerge from their dens and hibernation.

Alward is hunting with Dr Gerald Warnock, one of the world’s top award-winning hunters. Together they locate a bear’s den – and spot a bear that had clearly only recently emerged from it. Alward and Warnock go in pursuit on their sleds. The bear hears them, however, and tries to run away as fast as he can.

“The next few minutes of that chase were exciting,” writes Alward, as their sled is pulled along by a snowmobile at full throttle.

“When we were about 150 yards award, I jumped off the machine and shot the bear.”

The obligatory selfies are taken. Alward and Warnock kneel behind the bear. Alward is holding his rifle, the muzzle pointing skywards. It had a “luxurious coat of hair,” Alward notes.

Warnock goes home after the hunt. Alward remains, however – as he has a new target in mind: “I wanted to take a seal.”

Alward and the guides load up and get ready to set off.

“I drove the snowmobiles to the nesting grounds and found the seals sunning themselves on the edges of the ice. After watching literally thousands of geese landing, flying around, and on the water, I picked out a seal and shot it.”

Next stop on his route is Pakistan to hunt Chinkara gazelles and Punjab urials.

“I would be the first trophy hunter to hunt there since a disease carried by camels had halved its herd of eight hundred urial three years earlier,” he notes with pride.

He finds a large ram which he decides to shoot.

“We waited a few minutes until the ram I wanted stepped away from the others, then I shot it. The animal dropped on the spot, and my guide – as guides everywhere do – grinned and slapped me on my back.

“Its horns were 23 ½ inches long and would later rank number fifteen in the SCI All-Time Record Book of Trophy Animals. I was glad to add it to my collection.”

He concludes the trip by shooting a Urial, a Kennion gazelle, and a Sind ibex. “It was not as large as I’d hoped to take, but I was thankful that I was able to add it to my collection.”

Alward’s next port of call is Sudan, where he aims to shoot 5 of the 24 species of gazelle in SCI’s Record Book. His Red-fronted gazelle would rank number 3 in the world, while his Dorcas gazelle and Eritrean gazelle would both rank 14th.

After that, he flies to England to hunt deer with Kevin Downer Sporting, followed by a trip to Greenland to hunt muskox, after which he takes his 15-year-old grandson Jeremy hunting in Africa.

“Every grandfather will know how I felt. I enjoyed seeing him take his first African animals far more than if I had shot them myself.”

He decides he wants to add another leopard to his collection, so has a zebra and impala killed to use as bait. In the end it his grandson Jeremy who gets the big cat.

“Jeremy walked in with a leopard on his shoulder. It was a great moment to share. I was as proud of Jeremy as he was with his cat.”

At the end of the season, Alward writes: “It had been quite a year. I’d hunted in eight countries in Africa and Europe and had taken fine specimens.”

Alward is presented with the Weatherby Award at a gala dinner the following year. He continues his quest for more trophies, however.

One animal at the top of his list is a jaguar – an animal so rare that, nowadays, it is no longer legal for trophy hunters to shoot them. He fails however. “I would not have been able to ship it home, anyway. I only wanted to experience the hunt.”

His next hunt is for yet another bear, this time in Turkey. Alward’s guide has laid out bait while he sits in a stand behind a blind. The bait seems to have worked.

“I found the bear in my scope and sent it rolling down the mountain at my shot. It didn’t stop rolling until it reached the brush across a little creek below us.”

Alward walks down the hill in search of the animal. “There was quite a bit of blood, but the bear was gone.”

Disappointed, Alward waits for another bear to appear.

“I finally shot a bear the fourth night I was there. It was an old boar, and I shot it on the same hillside where I had lost the first bear. As with the first bear, it rolled all the way down to the creek when I shot. This time, however, it did not get up and walk away.

“My guides skinned it and boiled its skull that evening.”

From here he flies to Russia to shoot a Karaganda argali, a type of wild sheep found exclusively in eastern Kazakhstan. Alward’s new trophy enters the SCI Record Book at number three.

The season comes to an end. “I’d gone swimming in Antarctica and had hunted in Alaska, Bolivia, Ecuador, Turkey, Kazakhstan, Costa Rica, and Mexico.

“It had been a full year.”

The following year he has another chance to shoot a jaguar, although this time it would be darted with a tranquilizer rather than killed outright.

Alward’s guide stakes some live goats to the ground in order to lure the jaguar towards them. It isn’t long before one of the helpless goats is killed by a jaguar.

“We found the jaguar’s kill and put the dogs on its trail. They were out of sight in an instant, barking and howling constantly as they ran off. A few minutes later, we could hear them barking.”

They have chased the jaguar up a tree. The big cat is now trapped.

“As we approached, the jaguar roared. It was nothing like the roar of a lion, but it was a thrilling sound.”

When he looks up, Alward sees that it’s a female with a young cub. He decides to shoot it nonetheless. The dogs are recalled “to keep them from injuring the female or killing the cub on the ground.”

Alward waits until he has a clear shot.

“I sent a dart into the jaguar’s rump.

“The cat merely climbed higher in the tree; the dart seemingly had no effect.”

The guide tells Alward to be patient, however.

“Sure enough, after at least three or four minutes, the jaguar became groggy and started moving its head from side to side. It lost its balance and dropped to the ground.

“We made the usual ‘trophy’ photographs, as I held the cat’s head.”

The animal is injected with an antidote while Alward and the rest of the group retreat. It wakes up and, after a shaky start, eventually makes its way back into the jungle.

Alward has another unusual animal on his shopping list: the Atlantic walrus. “We searched for a light-colored male with long tusks,” he explains.

They spot one on a floe.

“I slipped my rifle out of the case I was using to protect it from the water and loaded it with 25-grain Nosler Partition bullets – my favorite load for heavy game with my Sako .338 Winchester Magnum.

“I put the cross hairs of my 1.56X Schmidt & Bender scope where the brain was supposed to be, waited until everyone in the boat had stopped moving, and squeezed the trigger.

“At the shot my walrus stiffened, then suddenly relaxes, without moving an inch.”

They tie a rope to the dead animal and tow it to another floe.

“I was awed by the size of the animal. It was more than ten feet long and weighed nearly two tons. Its tusks were twenty inches long.”

Hawaii is next, another country with no indigenous ‘big game’ animals – they have had to be introduced by hunters – followed by a return to Russia for another bear. He also flies to Pakistan and Iran to shoot wild sheep.

Alward ends the book by listing some of his achievements, including 277 SCI Record Book Entries. He then goes on to list every animal shot, where he shot it, and the date of the kill. The list runs to 7 pages – and comes to 345 individual animals.

His trophy rooms are testimony to his many years of shooting virtually every wild animal species on the planet. [2] A number of zebra skins form a near-continuous carpet across the floor. On one side, a lion and a leopard look on watchfully over a cluster of deer huddled in the middle of the floor.

A large elephant’s head, complete with trunk and tusks, protrudes from one wall. Beneath it is another leopard. In another room, a polar bear walks over a seal while a wolf looks on. Seabirds mingle with a bobcat.

In another area, a group of zebra skin-covered stools form a semi-circle around two large elephant tusks in the center. A gazelle appears to be jumping playfully through them, as if they were a circus hoop.

There are lions, zebra heads, cheetahs, and leopards. The bodies or a large brown bear, a polar bear, and a wolf.

A set of 4 stools has been made from elephant feet covered with zebra skins.

References:

[1] “To heck with it, I’m going hunting”, Arnold Alward. Safari Press, 2004

[2] “Great Hunters: Their Trophy Rooms & Collections”, Volume 1 1997. Safari Press